Will vs Technology

Where I, William Rudenmalm, document my quixotic struggle against technology.

The Implicit — Explicit Gap

July 27, 2013 A fundamental principle of Modern Psychology is the division of the mind into Explicit and Implicit. The explcit processes are those involving the conscious thought and in a sense we are always aware of them. Implicit processes, on the other hand, are more automated, and aren’t as dependent on concious thought. These systems, while interconnected, still have some degree of separation. The information richness of the information traveling between the systems is limited. Understanding the difference of between the two is important to properly design interactive systems. This article discusses the Implicit — Explicit gap from the perspective of designing information systems. I present two case-studies: The first to show-case how easy it is to make mistakes that can threaten the viability of a product as a whole. The second to show-case how the gap can be successfully bridged.

The human brain has two levels of mental processes, implicit and explicit. Implicit processes are performed without conscious control and relatively fast. Explicit processes are much slower and are essentially what makes up conscious thought. Explicit processes include verbal communication, reading, and writing — most complex tasks involve explicit processing. It also includes memory for knowledge, for example, knowing that constructors in Python are methods called init would be an explicit memory. Implicit processes on the other hand are different. They involve emotions, non-verbal communication and the heat-of-the-moment decisions that have dramatic consequences for our lives. Intrestingly they also form strong implicit associations for sensory impressions. For example, we tend to strongly associate emotions with smells. A smell can bring repaint a vivid picture of exactly how we felt at a certain moment. People often make the mistake of assuming that the, The implicit, fast-thinking functions, emotional part of the brain takes a less important role in our modern lives. Such an assumption, while understandable, is completely and utterly wrong. The “primordial brain” plays as big a role to us now as it has ever done. They in no way subordinate to the explicit systems.

The reason for the divide between implicit and explicit seems to be to allow the slower explicit systems to be adaptable. By letting the implicit systems handle quick decisions, the explicit systems can be more slower but process information in greater depth. This also means that explicit knowledge can be applied to novel situations in a way that implicit knowledge cannot. Discussing the evolutionary reasons of this split is as is the case with most evolutionary discussions, of course dubious. This because there is no way to establish what environmental effects produced which adaptations. No matter the origins of the split it has clearly been immensely successful.

Case Study 1: Sharing you mood

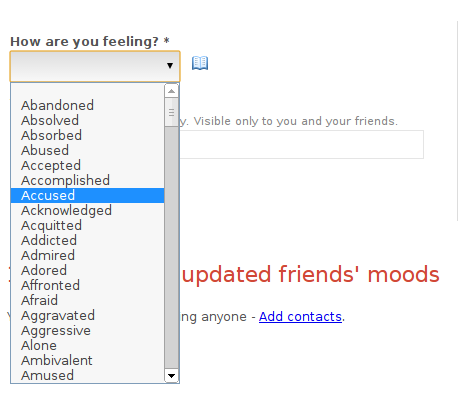

For the first case study I will be discussing a service that allows its users to share their mood. It provides a way to share information about your mood to your friends. The idea in and of itself sounds reasonable — telling your friends how you feel and getting to know how they feel is central to interpersonal relations. The mechanic for following is similar to that of Twitter. The user posts his mood by simply selecting it from an alphabetically ordered select box with hundreds of emotions. The user can optionally attach the reason as to why he or she is feeling that way. The posts then show up in a twitter-like time-line and on the front-page, a fire-hose showing all the latest posts.

The main problem with the service has to do with how emotions are selected. First of all, a plain alphabetical ordering doesn’t make sense because the user doesn’t know exactly which phrase he or she wants to post, and if it is even in their list of emotions. To make things even more absurd the user is offered a dictionary with short definitions for the words. A simple yet effective solution to this problem would be to simply let the user pick from twenty or so emoticons and simply clicking the one expressing how they feel. The service by making the user having to decide on a find a word from the list forces them to try to bridge the gap between the implicit and explicit systems. This makes it both difficult and time-consuming to post his or her mood. This interaction lies at the very heart of the service’s value proposition, and the lack of proper interaction design harms the product as a whole.

Case Study 2: Emoji on iOS

For the second case study I will dicuss emoji as implemented in Apple’s iOS operating system. Emoji are very popular with iOS users, most likely owning to the intuitive interaction design. Emoji is implemented using iOS’es system for international keyboards. The user simply taps the international keyboards button and the Emoji keyboard and the Emoji keyboard appears in place of the normal keyboard. While the assoication between expressing emotions and typing in other languages seems a bit odd and quite frankly bad UI design. The reason for it being considered an international keyboard has to do with the fact that prior to iOS 4.3 emoji were used only the Japanese language keyboards. The use of emoji outside Japan, however, grew and Apple made the keyboard a standard feature.

When the user wants to type an emoji character they are presented with a grid of images, each one representing an emoji character. Because of the limited space on the screen, users have to swipe between several pages of emoji characters. The user is also given a recently-used page showing the most recently used Emoji. While there are certainly things that can be improved with the UI for Emoji in iOS, they do get the most important things right. Because the images shown, that is, the actual emoji, are emotional, the user simply has to tap the one matching his or her emotional state. Without being having to rely on the explicit systems.

Designing for implicit systems

If your application relies on information processed by implicit systems you need to consider the differences between implicit and explicit systems. For most applications, information from the users explicit systems are used as input. In these cases, it seems more traditional UIs are sufficient.

Once we start dealing with information that is processed by implicit systems we get into trouble. Normal labels, textboxes and menus are easy to implement, and we often reach for these components when designing systems. To properly design for implicit systems means using images in addition to text. Images don’t require any language processing, prior to recognition. We also need to ensure that these images are easily encoded in memory. This means using images low in complexity. Complexity in general and geometric complexity in particular, make images hard to encode into memory. This needs to be balanced the need for the images to be recognizable. This has been a matter of some debate in the Human Computer interaction literature. In practice other considerations also come into play such as product branding. The issue of how to construct icons is, indeed, a challenge and has to be decided on a product by product basis.

In addition to designing the user-interface, so as to be useful to the implicit systems. An understanding of the nature of the information that the users are going to share in order to use your service needs to guide the design of the user experience. Failing to taking this into perspective, you end up with a product that might look great on paper, but completely fails to win over users.

Further Reading

If you enjoyed this article, here are a few books you might find interesting.

William Rudenmalm

Technologist at Sobel Software Research

William Rudenmalm is a european technologist passionate about the next big thing and the people building it. William is particularly interested in scaling engineering organizations and navigating trade offs of architecture and velocity. In the field of computer science, his expertise lies in distributed systems, scalability and machine learning. Among the technologies William is particularly excited about are Kubernetes, Rust, nats, Kafka and neo4j.